I’ve always been fascinated with pitchers.

Even as a hitter most of my life, I’ve always loved studying pitchers – their tendencies, their pitch makeup, how they operate. It’s fascinating to me, and I have always believed there’s a distinct advantage for a hitter in learning how a pitcher pitches. Because of this, a lot of the articles I write have centered around pitchers: Carson Fulmer, Lucas Giolito, Alex Colome, Carlos Rodon, and Reynaldo Lopez. Today, we get to one of my favorite Sox pitchers, Dylan Cease.

Dylan Cease has been an analytics darling since he was in the Cubs’ system. However, Cease has struggled to gain his footing to start his big league career. While it is far too early to panic or worry about Cease long-term, I think there’s something valuable we can all try to learn: what is holding Dylan Cease back from reaching his potential at this point in time?

When I started this article, I genuinely had no clue. But rather than do all the research first and then put together an article, I took it a different route. I decided to write my article as I did the analysis, in hopes of showing all of you the process I walk through when writing an article/analyzing a player. I’m hoping I can teach you a few things, and I hope detailing my process like this will help all of you make suggestions for what I can improve. By the end though, I promise we will come to some sort of conclusion about Dylan Cease.

With that, let’s begin.

The Video

Most of the time, my analysis starts with something I see. And, in the case of Dylan Cease, I’ve seen a lot of the following this year thus far:

Fastballs

Curveball

Slider

Changeup

What are your thoughts? Here are mine:

1) Even with a fastball that routinely hits 98-99 mph and is located pretty well, teams are making pretty solid contact with it. This is interesting to me.

2) Cease’s curve has either been spiked this year or has been a hanger over the plate. It doesn’t seem to fool many hitters, perhaps due to his inability to throw it for a strike when he needs to.

3) Cease’s best offspeed, by far, is his slider. It’s phenomenal.

4) Cease’s changeup, while solid enough to generate swing and misses, is often poorly located over the heart of the plate.

The real question is this: is there any statistical evidence to back up what I’m saying? If there is, can we get to the root of Cease’s problems by diving into the data? That’s where we will go next.

Cease’s Early Season Numbers

Cease so far this season is 4-1 with a 3.16 ERA. This, on the surface, is a pretty solid start to the season in most arguments. However, looking under the hood, there’s a lot we can learn. Let’s start with Fangraphs.

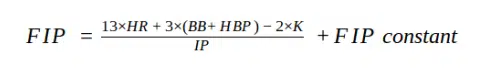

Though there are quite a few numbers there that raise eyebrows, the one I want to start the focus on here is Cease’s FIP. FIP is something we’ve all talked about before, but here’s the short and quick definition: FIP basically tried to approximate a pitcher’s ERA based on what he can directly control – home runs, walks, and strikeouts. FIP assumes that the defense behind a pitcher is league average. This means that, over the course of the season, we assume that those stellar plays that save runs balance out with those horrible balls that a shortstop will boot and cost the pitcher a run. Basically, FIP is a way to try and remove luck – both good and bad – from the evaluation of a pitcher. Here’s the formula:

The FIP Constant changes by year and incorporates League ERA. Its calculation is not important here. But, why focus on FIP? Well, if a pitcher is getting super lucky or super unlucky, the difference between a pitcher’s FIP and ERA will often tell that story. In this case, Cease’s ERA is a solid 3.16. However, his FIP is almost three runs higher at 6.14. This would suggest that Cease is “over-performing,” or getting lucky pretty often to start this season. This would be a cause of concern for Sox fans and may point towards a negative regression for Cease.

Now, let’s try and see how we get to Cease’s FIP. Remember, it’s based off of home runs, walks, and strikeouts. Let’s take a look at Cease’s profile on Baseball Savant from both 2019 and 2020. See if you can point out what one of the main drivers for Cease’s 6.14 FIP might be:

Did you get it? If you guessed his K%, you’d be correct. Cease has only struck out 15.4% of batters this season. As you can see above, that’s in the 17th percentile for the season. Last year, as a comparison, he struck out 25% of batters. This, combined with his pretty high walk rate of 8%, combines to give you a pretty high FIP. If you’re not striking out hitters, and you’re walking a fair amount, you’re putting a lot of runners on base and leaving yourself more exposed to luck in the form of relying on your defense to get the job done behind you. This is why we say, “A pitcher’s ERA tends towards his FIP.”

What are some other things we can learn from Cease’s Fangraphs page and Baseball Savant profile? Here’s what I think:

1) Cease’s GB% is 32% this year. That’s INCREDIBLY low for him, considering the lowest it’s ever been throughout his professional career is 42%. Less ground balls and less strikeouts (which, we’ve already established) naturally leads to more balls in the air.

2) With hitters hitting more balls in the air, the average exit velocity on balls it in play against Cease is 89 mph. This is in just the 40th percentile. However, interestingly enough, Cease’s Hard Hit % (% of balls hit against him over 95 mph) is 33%. This is down from 37% last year and is in the 62nd percentile. So, not as bad as the average exit velo, but not great. It speaks to the fact that hitters aren’t that fooled by Cease’s stuff, but he’s still overpowering hitters.

3) With more balls in play being hit harder, Cease’s FIP of 6.14 starts to make a lot more sense. Line drives are finding gloves, hitters are just getting under balls, and the shift is likely working in Cease’s favor. All signs of “good luck.”

Now we have to answer a few new questions:

1) Why is Cease striking out less hitters this year?

2) How lucky is Cease actually getting when striking out less hitters?

3) Are there causes for long-term concern for Cease? If so, how can he remedy these concerns?

Now, we get into the fun part of this: the pitch data.

Cease’s Pitch Data

Now comes the fun part: diving into the pitch data. There’s always some interesting things that can be learned from it. Let’s start by taking a look at some of Cease’s peripherals on Baseball Savant.

I highlighted some of the main columns that I’ll break down:

1) The average Launch Angle on balls in play against Cease is up 7 percentage points. That’s not great, not great at all.

2) Along with the high Launch Angle is coming a much higher Sweet Spot % – meaning hitters are hitting the ball “on the sweet spot” almost 40% of the time.

3) Hitters’ wOBA against Cease is already incredibly high at .359. According to the data on hits against him, it could even have been higher (.378 xWOBA).

4) Looking at xWOBACON (xWOBA on Contact), .415 is astronomically high. wOBA is a version on on-base percentage, so you can understand how high a .415 xwOBA on contact is.

It boils down to this: hitters are seeing the ball well against Cease, and these numbers show it. His ERA is 3.16. His xERA (Expected ERA) is 5.98. This follows the exact same “luck” narrative that we started with by examining his ERA/FIP differential.

As you can see, all of the above numbers are higher than last year. Even though there are similarities in wOBA and xwOBACON, there has clearly been a step back for Cease when attempting to avoid quality contact. So, from here we have to ask: has anything changed about any of Cease’s pitches from year-to-year? Let’s take a look:

Find anything interesting in these two graphics? The first graphic shows the movement on Cease’s pitches – both horizontally and vertically – and the second graphic gives a better idea of how hitters are doing on each type of pitch against Cease. Here’s what I learned from these two graphs:

1) Year-over-year, very little changed on each of Cease’s pitches in terms of movement. His curveball and slider continue to be his strongest pitches in terms of movement (more to come on the fastball soon). So, we can rule out any drastic changes in pitches to explain Cease’s increase in solid contact.

2) Cease’s changeup has become a HUGE problem to start the season. Hitters are hitting .400 against it, and according to xBA, they should be hitting even better than that. It doesn’t have the best pitch movement, but as evidenced by 2019’s BA against it, it can be effective. It’s a pretty rough pitch right now, but why?

3) Cease’s curveball isn’t generating any swing and misses. This doesn’t make sense either. Or does it?

So, let’s focus on Cease’s curveball and changeup. What’s the story here?

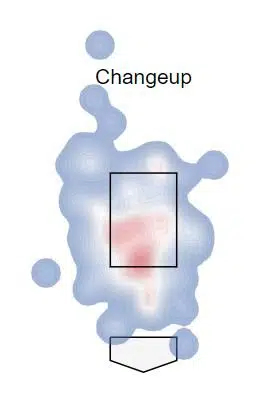

Changeup

2019

2020

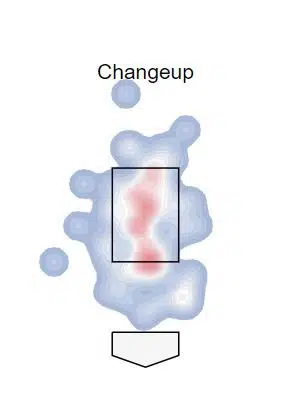

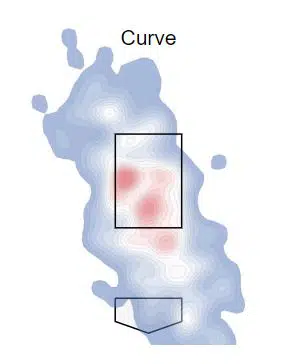

Curveball

2019

2020

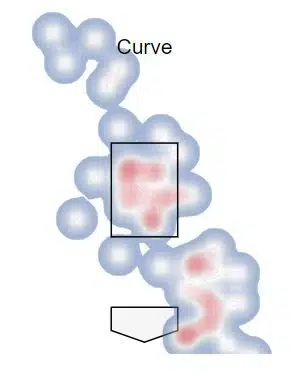

And, now we’ve come to a solution. Cease’s pitches have a lot of good movement on them. However, as you could’ve probably guessed, the location has been less than stellar. Hitters aren’t swinging and missing at his curveball because it’s either 1) a get-me-over curveball early in the count (red heat zone in the middle of the plate), or 2) a curveball that’s spiked so badly that it never threatens the zone (red heat zone down and away). It’s essentially a “show-me” pitch right now. As for the changeup, I think it’s fairly obvious that Cease needs to work on locating the pitch a bit closer to how it was back in 2019. This is nothing new for Cease: it’s always been about location, location, location.

If Cease locates his changeup and curveball better, it will not only benefit each of those pitches, but his slider and fastball as well. Hitters aren’t considering the curveball a competitive pitch currently, and his changeup finds the center of the plate way too often to be as effective as it could be due to his pretty excellent pitch tunneling.

Cease’s Fastball, Spin Rate, and Spin Efficiency

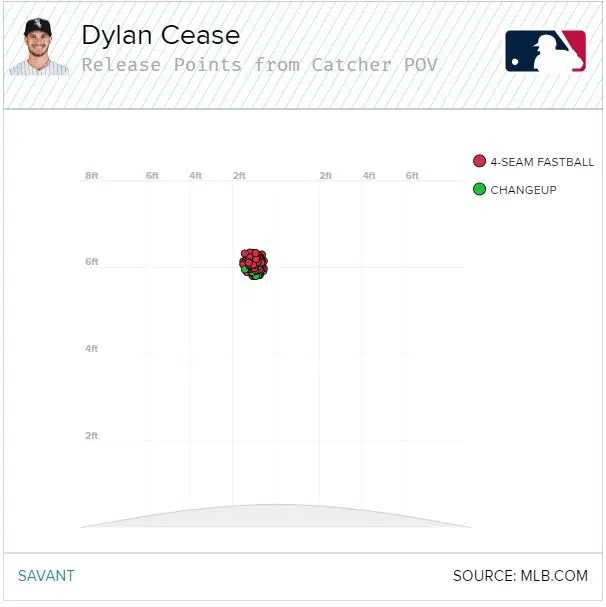

We still haven’t solved one last pesky issue: that fastball. Swings and misses on offspeed are clearly down because of poor location. But what about his fastball? It makes no sense. Cease’s spin rate on his fastball is among league leaders, and it only increased this season. Or, does it all make sense? Allow me to introduce you to Spin Rate Level 200: Spin Efficiency.

While raw spin – what we all refer to as spin rate – tells us how well a player physically can spin the ball, this number doesn’t tell the whole story. There are four types of spin that a player can place on the ball: backspin, topspin, sidespin, and gyroscopic spin. To understand each of these types of spin, grab a baseball, and follow along with me.

1) Backspin: grip a four-seam fastball. Mimic the spin that would be created if you threw that ball. That’s backspin.

2) Topspin: grip a curveball. Mimic the spin. That’s topspin.

3) Sidespin: grip a slider. Mimic the spin. That’s sidespin. Sidespin also helps the horizontal movement on a fastball – Reynaldo Lopez likely has a lot of this.

4) Gyroscopic Spin: hard to imagine with a baseball. Think of a perfectly thrown spiral on a football. That type of spin is gyroscopic.

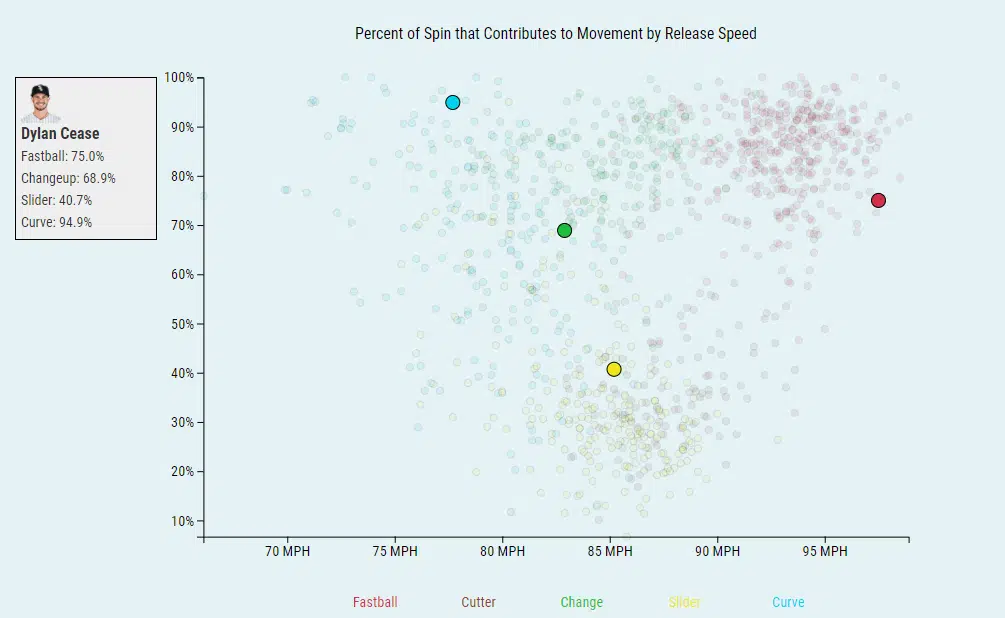

What’s the point of all this? Well, only three of those types of spin have an effect on the ball as it travels through the air: backspin, topspin, and sidespin. Higher measurements of these will indeed increase movement – either vertically or horizontally as we discussed above. Gyroscopic spin, on the other hand, has almost no effect on the ball. This leads into Spin Efficiency: what percentage of the movement that you put on your pitches actually affects its movement – what percentage of the Spin Rate is topspin, backspin, or sidespin?

Why is this important? If a fastball doesn’t have a lot of backspin, it won’t cause that “rise” effect for hitters. In other words, it’s a “flat” fastball, even if it has other types of spin. For example, the Spin Efficiency on Lucas Giolito’s fastball is 92%. This means, to simplify a bit, that 92% of the spin is either backspin, topspin, or sidespin. Most of that will actually be backspin, which causes the vertical movement (“rise”) Giolito gets on his fastball that has made the high fastball such a successful pitch for him.

What about Dylan Cease?

Only 75%. Despite having a spin rate that is among the highest in the league on his fastball, Dylan Cease is not getting enough backspin on his fastball.

I’m not just making this up either. Remember Cease talked about how his fastball was “cutting” on him last year? Well, of the three fastball variants, cutters will have the lowest spin efficiency since they employ the most gyroscopic spin in the fastball group. In other words, Dylan Cease’s fastball is still cutting on him a bit. This has essentially flattened out his fastball which, when combined with an inability to locate his plus-plus breaking stuff, has negated the effectiveness of his fastball. That’s why Cease can make good pitches like the ones in the videos way back above and still get quality contact against them – hitters are spitting on offspeed, and despite how fast he throws his fastball, hitters can square up “flat” fastballs. Just ask Reynaldo Lopez.

So, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is that Dylan Cease has the ability to fix his pitches. He already has an elite ability to spin the baseball. Now it’s about getting back in the pitching lab during the offseason and finding a grip/mechanics that allows him to maximize the spin efficiency on his fastball. The bad news? It has to wait until the offseason. This is not likely to be an in-season adjustment for Cease. What he can adjust, however, is working to locate his offspeed better to help out his fastball.

Let’s Bring This All Together

Wow, we talked about a lot, didn’t we? And the fun part was we took the journey together. Let’s go back to our original four takeaways from the video, and see what we learned from the data.

1) Even with a fastball that routinely hits 98-99 mph and is located pretty well, teams are making pretty solid contact with Cease’s fastball. This is interesting to me.

We talked about it just above – this comes back to Spin Efficiency and a lack of offspeed effectiveness. Cease needs to work on creating more backspin on his fastball. Until he can do that this offseason, he will need to keep hitters off his fastball with good location of his offspeed.

2) Cease’s curve has either been spiked this year or has been a hanger over the plate. It doesn’t seem to fool many hitters, perhaps due to his inability to throw it for a strike when he needs to.

This was spot on. Cease has yet to register a swinging strike on his curveball. In order to return it to its 2019 effectiveness, he will need to find a way to locate it just outside of the zone, instead of 5 feet out of the zone. It’s either been a “get-me over” pitch or spiked. He needs to work on this.

3) Cease’s best offspeed, by far, is his slider. It’s phenomenal.

This holds true. Great horizontal and vertical movement, and a .167 BA against. I know we all love Cease’s curveball, but I think his slider will end up being his best breaking pitch.

4) Cease’s changeup, while solid enough to get swing and misses, is often poorly located over the heart of the plate.

Oh yeah, we were definitely right on this one. Cease’s curveball and changeup, as we discussed above, will be the keys to his success. It helps keep hitters off of his fastball, which is “flatter” than we might expect.

Because of all that we listed above, it becomes clear why Dylan Cease’s 3.16 ERA doesn’t match up with his 6.14 FIP. Hitters are hitting the ball harder and in the air more. This doesn’t bode well for long-term success, but these factors can be mitigated with a greater control of his changeup and curveball. Cease’s elite offspeed pitches have me less worried about his fastball than someone like Reynaldo Lopez. But here is also a good point at which to remind people Cease will only be making his 20th major league start today. In other words, maybe “worried” isn’t the right word for Cease yet.

Cease’s next test is today against his former team. I expect him to be amped up to start this game, meaning you will likely see him missing way up a lot in the first inning. My hope is that he is able to maintain his composure. The bad news is that the Cubs work the count incredibly well. Cease cannot afford to nibble on the corners of the plate. He needs to display a command for each of his pitches early, lest the Cubs work the count and have him out after just a few innings. Cease has all the tools to be a top of the rotation guy – it’s about refining his craft at this point, which comes with time, work, and experience.

I know this was a more in-depth article than usual, but I do hope you learned something along the way that you can take and apply to other pitchers. If you have any questions, or any thoughts on how I can improve how I analyze pitchers, reach out and tell me!

The biggest lesson here is this: we used the data to build on what we saw with our eyes. We also used the data to uncover things our eyes would naturally miss – spin efficiency, for example. I hope this exercise not only taught you more about Dylan Cease and where his growth might come from over the rest of the year, but also the importance of using both data and your eyes when discussing/dissecting baseball. Your eyes help you determine where to focus your attention in the age of information, and the data catches what our eyes miss.

In other words, traditionalists and analysts can – and should – work together at the end of the day.

Thoughts? Let me know in the comments below or on Twitter! @jlazowski14

Featured Photo: Brandon Anderson (@b_son4)

My first thought on watching those videos was, “That fastball’s as flat as I’ve seen in a while. Just straight in there.” On a bad computer so couldn’t get the changeup one to show cleanly, but the numbers bear out that it’s flat, too. I think those two problems are leading to the rest of his struggles, really. If you have a flat fastball and changeup, a hitter can pick up the flatness immediately and now only has to adjust his timing. If your fastball is live, then he has to wait longer to decide and can get fooled more easily by sliders.

I will say, however, that I was impressed that, even though he had the bases loaded with no outs against the Cubs, he buckled down, got the K, and then got a double-play to escape the inning. When he first came up, he’d get in his own head and that would have been a 3+ run inning. He may have taken the loss against the Cubs, but he was a professional out there, which is a good sign and may contribute to the FIP/ERA disparity as well.

Cease displayed very good command as a power pitcher in the Carolina League.He was not known as a nibbler.I suspect the nibbling issue has come from Don Cooper.Like I said,he did not pitch that way in the minors.