“In the struggle for survival, the fittest win out at the expense of their rivals because they succeed in adapting themselves best to their environment.”

Charles Darwin

These words from Charles Darwin, friends, will be the ones that guide our conversation in this article. It is time for the White Sox to adapt and become comfortable with the unconventional.

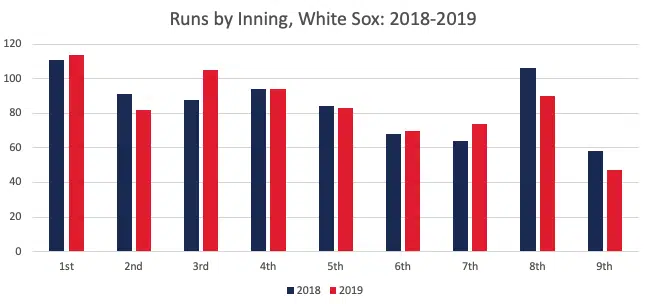

This is the era of offense. Pitching remains as dominant as ever, but runs are being scored and balls are being launched out of ballparks at record rates. Hitters are not allowing pitchers to settle into games early – in both 2018 and 2019, the first inning saw almost 100 more runs cross the plate than any other inning. How are team supposed to react to this? This is certainly not the era of “business as usual” operation. Something had to change.

The History of the Opener

Enter the “Opener.” Over two years ago, I wrote an article about this exact same topic. The idea of it is simple, and it’s one that’s been used by some of the best teams in the game: a high leverage relief pitcher (“Opener”) begins the game instead of your typical “Starter.” After an inning or two by your Opener, the typical Starting Pitcher is brought into the game. In essence, teams adjust the order in which pitchers pitch in the game.

What’s the point of this? It stems from this concept: the most important outs of the game aren’t necessarily in the late innings. Think about it: if a team loses 4-0, and all four runs were scored against them in the first inning, it really doesn’t matter who was available to pitch in the 8th and 9th that day – those typical back-of-the-bullpen arms were completely wasted. The “most important outs” they would typically be saved for in those late innings actually occurred in the first inning. Another way to describe these “most important outs” are “high leverage” situations, and these can occur at any point in the game where it feels the game could shift at any moment. Again, this all goes back to the run-scoring environment of present-day baseball: more runs are being scored earlier in the game.

The Rays kickstarted this phenomenon back in 2018 – May 19, 2018, to be exact, when closer Sergio Romo started the game against the Angels and gave up no runs. The Rays won that game 5-3, and Romo proceeded to open the next night as well: 1.1 IP, no runs. Romo would go on to open 3 of the next 7 games for the Rays as well, and the Rays would go on to give up the fifth fewest first inning runs in baseball that year.

This strategy has helped one young pitcher in particular for the Rays, Ryan Yarbrough. Back in 2018, Yarbrough was often the next pitcher brought in after an Opener. Now, with the Rays staff much stronger than that of 2018, Yarbrough is now a Starter – from the first inning on. This serves as as sign of growth for Yarbrough, and echoes the idea that an Opener strategy isn’t forever and isn’t for everyone.

The Rays certainly aren’t the only team to try this. In the 2018 AL Wild Card Game, Liam Hendricks served as the Opener for the Athletics. In that same year, Wade Miley threw to just one batter in Game 5 of the NLCS for the Brewers. In 2019, Chad Green opened 15 games for the Yankees – the team won 11 of those games. To cap it all off, the Angels threw a no-hitter on the day they honored Tyler Skaggs. The opener was Taylor Cole; Felix Pena finished the last seven innings.

The White Sox and the First Inning

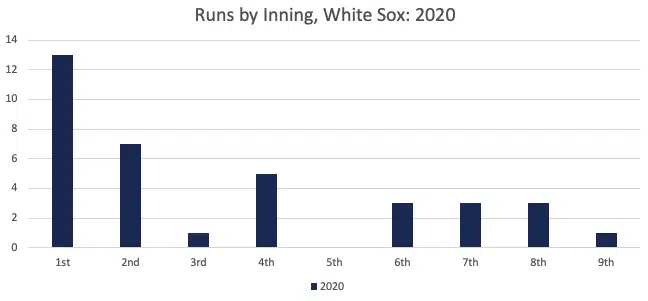

We now know that the first inning is a troublesome inning for A LOT of teams in baseball and that the Opener strategy has been a popular remedy to that. How do the White Sox fare in the first inning in recent seasons? You can probably guess, but I have the data anyway:

Surprise, surprise, the White Sox have historically struggled in the first inning. In both 2018 and 2019, it was the inning in which the most runs were scored off the White Sox. Thus far in 2020, they have been the worst team in baseball in terms of runs allowed in the first inning. By all accounts, it appears that the White Sox seem like the type of team that would be considering an Opener strategy. Indeed, they are: they have a young, talented, but inexperienced rotation with some quality depth in the bullpen. That’s a match made for the Opener strategy.

The White Sox and the Opener Strategy

So, if you’re still reading, your mind is at least open to seeing how the White Sox could adapt their current rotation to suit an Opener strategy. Excellent. So let’s map out what an ideal start to a typical turn through the rotation could look like for the White Sox, keeping in mind a few thing:

- The Opener strategy is not necessary for every pitcher on a roster; certainly, Gerrit Cole, Shane Bieber, Mike Clevinger, and the like don’t need Openers. They’re already maximizing their potential as players.

- The Opener strategy doesn’t last forever; rather, it is a short-term confidence builder for pitchers who are inexperienced or might typically struggle in a given inning.

- These Openers are just a suggestion; I outlined my reasoning for each pitcher within the section, but you could logically place any bullpen arm in the first few innings.

With that, let’s begin.

Game 1: Jace Fry 1-2 Innings, Lucas Giolito Follows

You’ll see a pattern develop by the end of this, but let’s start here. First, why is the Sox’ ace getting an Opener? Doesn’t that go against #1 above? Well, here’s the problem: Lucas Giolito’s career first inning ERA? 2018: 9.00, 2019: 4.66, 2020: 18.00. Yikes. Giolito could clearly benefit from facing hitters at the bottom of the order first before the lineup turns over. So, that’s why our Ace gets an Opener.

Why Jace Fry? I think they’re a good combination: Fry is a curveball heavy pitcher, while Giolito is FB/CH/SL combination. Those are two different pitch mixes that hitters will be facing early on in the game, keeping them off balance. I think this combination helps to get the best out of both of these pitchers.

Game 2: Dallas Keuchel Starts; No Opener

As I said before, not every pitcher will need an Opener. As a seasoned veteran, Keuchel has earned the right to start the game in the first inning. His track record is much stronger, and there is no clear evidence that he would see a substantial benefit from having a Opener come out before him. However, in theory, having a hard-throwing reliever start the game in front of the soft-tossing Keuchel is an intriguing idea. But, like I said, the Opener is not a one-size-fits-all strategy.

Game 3: Gio Gonzalez 3 Innings, Dane Dunning Follows

The third spot in the rotation is currently the most unknown; for now, Gio Gonzalez is the heir to the throne with Reynaldo Lopez’s injury. However, with Dane Dunning not too far away in Schaumburg, I don’t think it will be too long before his number is called. I think Dunning could become a stabilizing presence in this rotation if Lopez is out of commission for some time (I also think Dunning should have the spot long-term over Lopez, but I digress).

I think giving Gio Gonzalez one turn through the lineup maximizes his effectiveness, though his 2019 numbers don’t necessarily reflect this. However, his career numbers are much more in line with the typical line for a soft-tossing LHP: as the game goes on, they become less effective. So, one turn through the lineup serves as a perfect bridge to Dane Dunning, a hard-throwing RHP with some sharp breaking pitches.

Game 4: Aaron Bummer 1-2 Innings, Dylan Cease Follows

Dylan Cease is one pitcher who certainly gets better as the game goes along. Here’s how hitters have fared against him:

- First Time Through the Order: .426 wOBA

- Second Time Through the Order: .356 wOBA

- Third Time Through the Order: .270 wOBA

Following the lead that was started with Fry and Giolito, I think the combination of Bummer and Cease has the ability to be filthy. Bummer is a hard-throwing sinkerball pitcher, while Cease relies on a FB/CH/CB/SL mix that tends to find its way into the upper parts of the zone. With these two pitchers working in completely different parts of the zone, it will be difficult for hitters to adapt from pitcher to pitcher. This is where Cease could benefit from being eased into a game: facing the lower third of the order would allow Cease to focus on getting ahead and staying ahead before facing the heart of any team’s lineup.

Game 5: Jimmy Cordero 1-2 Innings, Carlos Rodon Follows

By the end here, I hope you caught the pattern: whichever hand the “Starter” throws with, the Opener was the opposite hand. Their “stuff” also complemented each other well. The goal is simple: cause hitters to need to make as many in-game adjustments as possible and make it more difficult for managers to stack the lineup depending on the starter.

This trend continues with Cordero/Rodon. As a right handed sinkerballer, Cordero is a stark contrast to the left-handed FB/CH/SL combination that Rodon features. Pairing the two of them maximizes the amount of adjustments hitters will have to make between the time they face Cordero and the time they face Rodon. This will allow Rodon to feel he can attack the zone early and get into a rhythm, preventing himself from falling behind and being consistently plagued by walks.

The beauty of the Opener strategy is that there are so many different options available to a manager. For example, Jace Fry pitching on a Monday as an Opener should not prevent him from pitching Tuesday as a late inning relief guy. The Opener strategy does not necessarily affect how a manager constructs his bullpen late in the game, adding to the appeal of this strategy. One, two, or three innings, it really doesn’t matter – all that matters is that this strategy allows the White Sox to put their young starters in the best position to succeed.

Baseball is All About Adjustments

Let’s turn this all the way back to Charles Darwin at the beginning. The environment the White Sox have is such: there’s a ton of talent that struggles to keep itself out of the big inning in the first. As a result, the White Sox have behind out of the gate in all four of their losses due to the first inning. The White Sox and Ricky Renteria can choose two respond in two ways:

- Continue to run the starters out there in normal fashion and hope everything starts to click together with more starts and more experience.

- Use an Opener for select starters until a starter feels comfortable working from the first inning on.

Not all teams should or will use Openers; teams that use Openers have identified some sort of weakness in their ball club that can be improved through the optimization of their pitching staff. Throwing an Opener isn’t necessarily a sign of a weak pitching staff; for the White Sox, it is the sign of a pitching staff that is inexperienced and working through some growing pains.

By now, I imagine the White Sox have evaluated themselves and understand there is a sizable gap between themselves and the Twins/Indians in the AL Central. At the same time, I can only hope the entire staff begins to adapt to the situation at hand, lest they be left behind as their enemies rise to the top and dominate the AL Central.

Another great quote to end it: “Adapt or die.” May the best teams win.

Thoughts? Comments? Let me know below or on Twitter! @jlazowski14

Featured Photo: Chicago White Sox (@whitesox) / Twitter

While a smaller concern, it allows the 2nd pitcher to pick up a win more easily. Ozzie was quite a character (to put it nicely) as a manager, but one thing he did that I always appreciated is whenever he could, he took his starters out when the worst they could do was a No Decision. Win or ND, not a loss. With an opener, the 2nd pitcher isn’t locked into a full five innings to be eligible for a win, and things like that can build confidence for young guys. It’s a little thing, but it is an added benefit.